During our time in NY, we sat down with New York-based architect and researcher Joseph Grima, director of Storefront for Art and Architecture. This becomes the first of a series of interviews to be done regarding Project-Sky and other relevant subjects that surround it. The result was an overwhelming insight on megacities, their future, and its inhabitants. Enjoy!

JG: Joseph Grima

JME: Jose Manuel Esparza

DFP: Daniel Fernandez Pascual

AU: Alvaro Urbano

JME: Being that you've lived in both London and New York, What are your thoughts on these cities and how would you say you relate to them?

JG: Something that I was thinking the other day, is how there is this whole new generation of people who don't necessarily spend their time in one city. They maybe live in NY but they spend just as much time elsewhere, but always inside cities and never outside the city. There's this coexistence of 2 worlds, the city and the extracity, which are not in 2 different places, there not distinct territories but they're kind of completely mixed up one and the other. The cities are just connected by airports and you can go fluidly from one to the other, skipping everything that's in between. And what emerges is a perception of something that goes even beyond the megalopolis. It's just one massive global city that you can flow between with very little consciousness of whatever's around it.

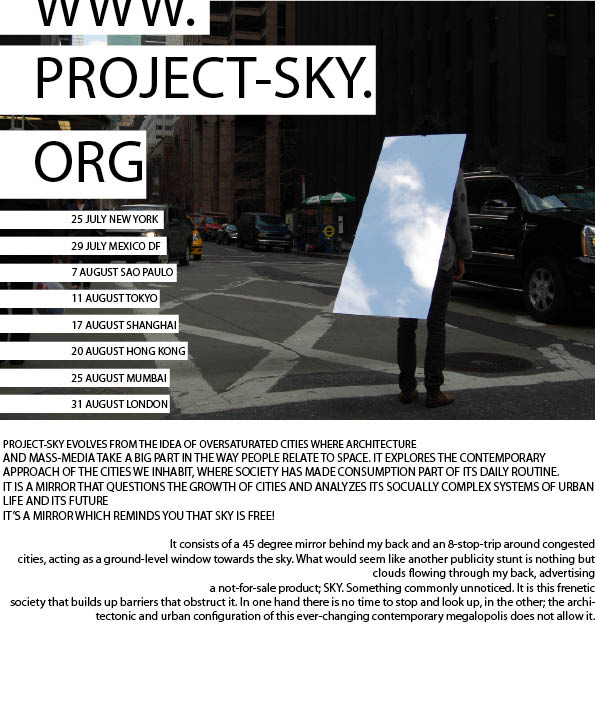

One of the things it think is really interesting about your project is that it exposes the fact that this is a very thin layer, they’re just like dots on the surface of the globe and even these dots are just 2 dimensional, totally horizontal all you have to do is look up and you are exposed to the fact that reality is 3 dimensional and that there’s kilometers and kilometers of air above, and there’s earth underneath you and you’re just kind of captured within this 2 dimensional reality that you assume to be almost limitless; and when your inside the city it could be continuous urbanism from here all the way to Berlin or to London for all that we know.

DFP: Regarding the different conceptions of societies and cities like London or NYC which 20 years ago were used as reference models for political or architectural movements to the world, and the fact that probably 10 years from now we’ll be living like Shanghai, and use this as a model for western societies, being they have lived a very concentrated development which we have lived in Europe or in the US in 100 years rather than in 5; Which differences would say they’ll be in the future for architecture and urbanism in the world? Who will copy who?

JG: One interesting thing is the semantic issue which relates to the word city. I think the word itself forms a lot of ideas of where we are, but if you think of one interesting fact, in some recent years there’s been this big whole tendency to try and look for a new word. Words like “conurbation” or “metropolitan region”. This kind of idea of something that’s not a city and is more than a city. It’s a region and at the same time not -a region traditionally would be rural in part- but this actually is a metropolitan region. So it’s something that’s as big as a region but at the same time metropolitan. These are those things that simply didn’t exist in a matter of decades ago. So there’s a semantic issue of how to talk about these things., how to visualize them in our minds, because we’re not really equipped yet on an experiential basis to be able to define them or to describe them even, so this is kind of an initial problem.

The interesting thing I think is happening is that new social devices are being invented and are coming to influence in the way people experience these cities. I had an interesting conversation with Minsuk Cho, architect from Seoul, which is one of the cities in Asia which is expanding most rapidly and is undergoing this very rapid, not in physical terms but rapid social evolution. The way people are living in the city as the city becomes progressively wealthier, and he was saying there’s this emergence, he did a project in which he proposed a new type of inhabitant. Instead of inventing a new type of building or a new type of city, he invented a new type of inhabitant who didn’t actually live in a single place, but would simply be engaged in this perpetual derived around the city in which he would sleep in hotel rooms that you can rent for a matter of hours, for blocks or for hours; not like prostitution hotels, but like capsule hotels, and all these public baths where you can go and not just to wash yourself, but there’s also yoga classes and gym classes and cultural events happening, and maybe this is a 30th floor of a skyscraper. There are all these public internet cafes where you can go and be completely connected to the rest of the world. You can go to the cinema and even there’s this kind of totally versatile fluid way of living the city. You can even earn a living by doing this without having a fixed job. So it’s quite an interesting project in which it reinvents not so much the physical nature of the city but the way that it’s experienced by its inhabitants. And I don’t think architects should be so presumptuous to think they can reinvent people’s lives, but I think there are ways in which the city can be rediscovered and reinvented in a way without actually engaging its physical structure. Without saying cities like Shanghai are in sustainable or like the Pearl River Delta needs to be transformed into a sort of, which is what Dubai does, it kind of tries to recreate the Manhattan experience of density and so on. And maybe that’s not the only model, maybe there are other models that are more interesting and I think that your point is very good, that actually the west is going to be learning from the east. And suburban America might learn from suburban China.

DFP: Do you think this global inhabitant is much more related to this megalopolis because airplanes put you in touch with a citizen much further away than with rural inhabitants? Do you think these two worlds borders will disappear?

JG: I think it’s a problematic. This of course, is a very very small minority of the world that really can just go to the airport and get in a plane and go somewhere. It’s insanely complicated for most of the world’s population. On the other hand I think that human being is a little bit like this famous internet generation motto which is “information wants to be free”, and that’s kind of the principle which has driven the web 2.0 evolution in a way. Ultimately I believe that human beings and culture and bodies also want to be free, and I think that it’s going to become increasingly difficult to contain and draw fences around mobility.

DFP: In this context, do you see huge skyscrapers and buildings as an interruption to this communication era. Is the way the city is planned thought for its inhabitants or against its inhabitants?

JG: I don’t think verticality in itself is a problem, I mean it’s extremely complex and I think it’s very much market driven. Related to what we were discussing before this idea of the idea of the emergence to the global city which is connected by whatever means of transportation. Within this global city you can imagine all this different districts. There’s the luxury district, the working district, the industrial district, the services district. So, in a way what is emerging is like the Asian cities which are the industrial productive districts from which all the goods are sent by ship to the rest of the world. Then there’s in India this kind of Services district with all the call centers and software development companies and so on where everything is kind of like the nerve center of the information network. And then there are places like Manhattan and London which are the chic residential neighborhoods. London even more than NY has become some quite shocking how it’s not for wealthy British, it’s for the wealthiest elite of the whole planet. The wealthiest people from every culture are there. And in NY as well, the only people who can really afford to buy in Manhattan are the ultra wealthy class, and of course what’s happening is, these cities are becoming huge gated communities were there’s much less social diversity, much less exchange. Even though Manhattan is in a way an incredibly socialist city, with its huge amount of tenement apartments with city-regulated rents and so on. It’s traditionally extremely socialist, and this is crumbling bit by bit. London doesn’t have any of that. It doesn’t have many of those social parachute safeguards. In London it’s even more extreme in a way. So in sense, I do think the architecture is a problem because the architecture that is being built here is all high rise luxury condos, that’s what NY is becoming famous for. And that’s very problematic for the urban fabric and what it implies.

DFP: Which role would public space or street play in the way these inhabitants live the city in relationship to these high condos?

JG: I don’t think at the end of the day, the high condos are architecturally a problem, I think that verticality and density are ultimately a good thing. I think the problem is a lack of social mix. As soon as it becomes to flat, and when the average wealth is extreme, all sorts of problems start to occur because there’s a schism with the surrounding neighborhoods to go across the bridge to Brooklyn or New Jersey and your kind of object poverty and that kind of contrast always spells danger and unrest.

And then in terms the way the city is inhabited I think that one of the great things about NY, and they’re some really great things about this city that kind of continue to live on. Like the fact there are so many small independent bars and cafes like Epistrophy which are run by just one or 2 people who make a good living and reasonable money in very small spaces. Independent, being that they’re not part of chains, and that’s what really keeps the neighborhoods alive. Services that aren’t too elitist, they’re not like chic clubs but just reasonable cafes, restaurants and that sort of thing; at least in this neighborhood. That’s something that NY has been much better in preserving than London for example, where that sort of scale of operation is being completely wiped out by chains and by very large restaurants that have a lot of financial backing. But yes, I think the great advantage of cities with very long history is that they have a strong instinct of self preservation, they’re very good of keeping, and surviving the ups and downs, and changes and so on. I think the DNA of this city is strong enough to be able to overcome the onslaught of the luxury condos that’s currently undergoing. But I it’s a problem, everyone wonders how far you can push the whole system before it starts to crumble under some weight.

AU: Would you say that the barriers that obstruct us to see the sky are more physical or psychological?

JG: I’d say defiantly psychological.

AU: And what do we have to do to change it?

JG: I think that the interesting thing about your sky project is the fact that it blends verticality and horizontality. Human being, being vertical, has a horizontal outlook on the world and the sky is inherently horizontal so it’s kind of parallel existence to our own. It’s really amazing actually how the great thing about your project, and I think the thing that stands out in the photographs, is how incredibly strong the contrast is with the surroundings. Your mirror basically succeeds in chopping out some pieces of sky and bringing them down into horizontal, and I think it really awakens people to how remarkable the sky is. The light level on the sky is so infinitely greater than the light level in all the surroundings. I really enjoy that contrast, it’s kind of like a wakeup call, and I think they are many little ways that art and architecture can do. I think that’s the great thing about art and architecture. I don’t think it’s up to the individual to find a way to incorporate this into their daily lives, the awareness of the sky. I don’t think it’s something that can be imposed or that we can architecturally invent buildings with 45% mirrors and suddenly everybody’s lives are changed. But I think that what your project does is remind people to simply look up.

I don’t’ think we should be necessarily too critical because it could become hypocritical very quickly. I mean there are worst periods in history than what we’re living in -despite the enormous crisis we’re facing-. There’s a lot that can also be done to improve. I think ultimately human beings want self optimization. It is possible to find a balance were we can still appreciate the great things about life and the great things about existence such as the sky above our heads without going into some sort of moralistic attack on the city. I mean, cities are great, and if you have the privilege of being in the position where you can travel to 5 cities in 3 months and do an art project, I think we should also be very appreciative of that and not be too critical. But I really like what you’re doing. Injecting a little bit of sky in the city. It’s like an urban collage.

1 comment:

what a cool interview!

complete, inspiring and a mind-lifter!

shame storefront will be closed for the month ill swing by nyc... oh well...

well done you lot!

-cousin (awaits you guys!)

Post a Comment